The mammalogy department at the Sam Noble Museum has spent the last year trying to determine precisely where the tri-colored bat occurs in central and western Oklahoma. As the state’s smallest species of bat, it is believed to live in all of Oklahoma, except for the Panhandle. However, it has only been documented in 31 of the state’s 77 counties.

“The tri-colored bat is not endangered, but the state has designated them as a species of special concern,” said Brandi S. Coyner, curatorial associate of mammals. “A major reason for current concern is because the disease, white-nose syndrome, has been killing bats by the millions in the northeastern United States. In Oklahoma, the tri-colored bat seems to be a common player when white-nose is found.”

The disease is caused by a fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd), that is found in Europe and China. It was first detected in the U.S. in 2006 in a cave in New York that adjoins a highly visited commercial cave. The fungus and white-nose syndrome have since been spreading like wildfire across the United States. In Oklahoma, three tri-colored bats in Delaware County were the first to test positive for the fungus in the state. Last year, a single positive sample from a tri-colored bat in Woodward County expanded the fungus’ known presence into western Oklahoma.

“Research shows that the fungus is moving progressively westward, but we haven’t seen many dying bats here in Oklahoma,” said Coyner. “The current hypothesis is that it’s a cold-weather fungus, so as you go farther south, it just can’t survive as well.”

Corroborating Coyner’s statement above, Hayley C. Lanier, assistant curator of mammals, says the fungus is mostly active during the winter season.

“In the winter, bats hibernate, and when they’re hibernating, their body downregulates their immune system,” explained Lanier. “That means that their immune system is basically inactive, and their bodies aren’t working to get rid of the fungus, allowing it to creep and spread throughout their bodies.”

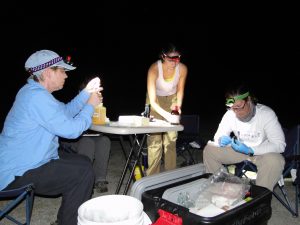

Coyner, mammalogy curator Janet K. Braun, one graduate student and two undergraduate students spent time this past summer traveling throughout the state of Oklahoma searching for the tri-colored bat. Using nets made out of fine mesh, similar to hairnets, the team spent time at 17 different locations in five counties this summer. Once a bat is caught, it’s carefully “worked up” which includes a physical examination, a search for external parasites and testing for the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome.

“When infected, the bat’s nose will be covered in white fungus, hence the name,” said Coyner. “Bats that survive infection will also have scars on their wings, which can be seen under ultraviolet light.”

To test a bat for the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome, a specially made swab, similar to a Q-tip, is run over the bat’s face and wing. The swab is placed inside a tube with sterile water and then frozen. Upon return to Norman, DNA is extracted from the swab. The results let the researchers know if the fungus is present, and if it is, in what quantities.

The mammalogy department has tested every bat they’ve caught so far, and none of the bats have tested positive for the fungus. The researchers are taking precautions in the field to prevent any cross-contamination, and to hopefully keep Oklahoma bats from becoming infected.

“When we catch a bat, anything that’s used to touch the bat is disposed of or decontaminated, so we don’t accidentally pass anything on to the next bat we catch,” said Coyner. “This is a precaution, since we don’t know whether that bat is positive or negative for the fungus.”

The research, funded by the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation, will continue through September 2021.