“In Caddo ceramics the art of the Southeast easily reached its apex, for while there are specimens of pottery from the Middle Mississippi region and Moundville which show as high technical excellence, there are none that, upon the whole, exhibit equal artistic feeling.” John R. Swanton, 1942 “The Caddos produced pottery ranking with the finest and most ornately decorated of any produced by an aboriginal culture in the United States” F. Todd Smith, 1995

We will never fully understand the underlying social and spiritual significance of the meanings intertwined within the designs of Caddo pottery. This knowledge was passed down orally and was not recorded by early European explorers, so it has since been partially lost through attempts by the United States government in the 19th and 20th centuries to overwhelm and assimilate the Caddo people. Caddo people began an earlier rapid change after their first contacts with Spanish colonists in the 1500s. Smallpox, measles, cholera and other European diseases ravaged the Caddo and reduced their population by 95 percent before 1700. Archaeological evidence reveals larger villages along the Arkansas, Red and Ouachita rivers were abandoned and a change from burial of elites only in mounds to community mortuaries during this time period.

Much cultural information has been lost from the past. However, modern day Caddo descendents are revitalizing their past culture, preserving what is known today of Caddo culture, as well as incorporating Caddo culture into a modern globalized world. Viewing the artwork of these ancient Caddo artisans requires an understanding and appreciation of these ever changing cultural contexts. In the past, the construction of Caddo ceramic vessels and designs did not take place in a vacuum, but occurred within the rich cultural interactions of the Caddo people. The Caddo of today as well as cultural anthropologists and archaeologists have uncovered clues to the cultural contexts that provided meaning to the Caddo potters of the past.

The Caddo became horticulturalists around 800 A.D. Their principle crop was maize. Other crops included beans, squash and native cultigens such as maygrass, amaranth, chenopods and sunflowers. Early Spanish accounts indicate they grew two corn crops a year. Unlike Western society, where blood relatives are recognized on both sides of the family, archaeologist have found that matrilineal kinships are more frequent in horticulture societies, such as Caddo. In matrilineal kinship, the principal relatives are those from the mother’s ancestors. Property is therefore passed down from mother to daughter. The mother/daughter relationships in these societies are precious in the passing of cultural knowledge.

The Caddo tribes were formed into communities of isolated homesteads, hamlets, and larger villages. The larger villages are identified by the construction of earthen mounds that were used for the foundation of temples, burials, and fire mounds. At these mounds civic services and special religious functions were held. The Caddo believed in the supreme deity called Ahahayo, meaning “Father above”. Ahahayo created the world, rewarded good and punished evil. The intentions of Ahahayo were communicated to the religious leader of the tribe called “xinesi”. Xinesi blessed the crops during planting, the construction of houses and was the leader during ceremonies and feasts. A perpetual fire was kept by xinesi in a temple near his house. At the temple the two divine children called “coninisi” were mediators between Ahahayo and xinesi. Besides the xinesi there were medicine men called “connas” who mended the sick and presided over burials.

The Caddo tribes were formed into communities of isolated homesteads, hamlets, and larger villages. The larger villages are identified by the construction of earthen mounds that were used for the foundation of temples, burials, and fire mounds. At these mounds civic services and special religious functions were held. The Caddo believed in the supreme deity called Ahahayo, meaning “Father above”. Ahahayo created the world, rewarded good and punished evil. The intentions of Ahahayo were communicated to the religious leader of the tribe called “xinesi”. Xinesi blessed the crops during planting, the construction of houses and was the leader during ceremonies and feasts. A perpetual fire was kept by xinesi in a temple near his house. At the temple the two divine children called “coninisi” were mediators between Ahahayo and xinesi. Besides the xinesi there were medicine men called “connas” who mended the sick and presided over burials.

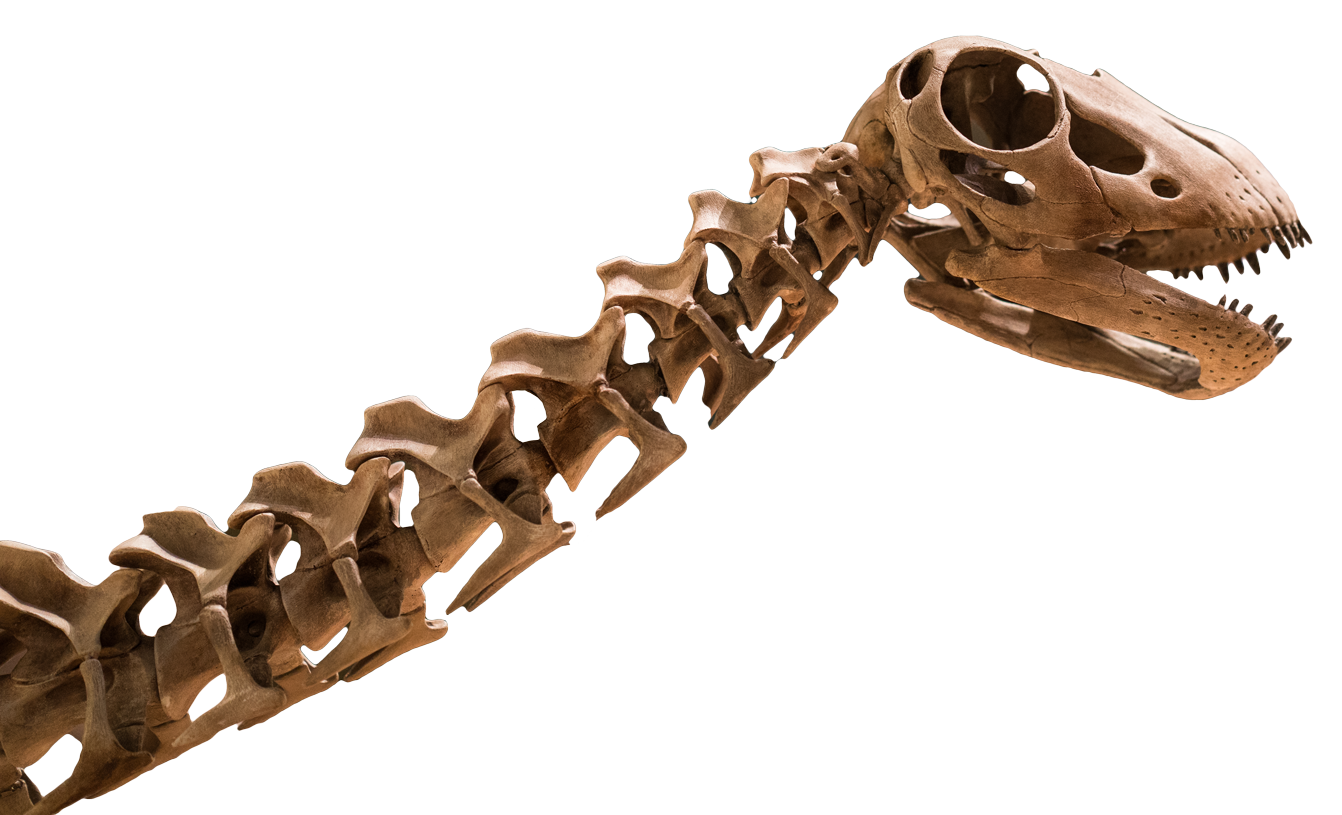

According to Caddo beliefs, after death the soul travels to the sky and enters the House of Death, presided over by Ahahayo. Here, the souls of the Caddo wait for the others on earth before entering another world to began anew. In most burial contexts, occur elaborately decorated ceramic vessels. These vessels held food and other supplies for the deceased while waiting to enter another world.

The word “Caddo” is a French abbreviation of the Caddo’s word Kadohadacho that means “real chief”. Before European contact, the word Caddo did not stand for the larger cultural entity that it is does today. Instead the Caddo were 25 separate —but related — groups of bands and tribes. These became organized into the Hasinai, Kadohadacho and Natchitoches after European contact. The tribes that occupied the Red River valley in Oklahoma were the Kadohadacho and Nasoni. The women potters of the Kadohadacho and Nasoni groups are the ones who made the pots on display in the online gallery.

The pieces in the online gallery are part of the George T. Wright collection. Wright compiled this collection through the purchase of ceramic vessels that had been unscientifcally recovered from a number of unknown sites principally from McCurtain County, Oklahoma and Red River County, Texas. From Wright’s notes, we know the majority of the pottery was obtained from burials. The maps below show the Caddo culture area, and a close up of the archaeological sites that occur in McCurtain and Red River counties.

The pieces in the online gallery are part of the George T. Wright collection. Wright compiled this collection through the purchase of ceramic vessels that had been unscientifcally recovered from a number of unknown sites principally from McCurtain County, Oklahoma and Red River County, Texas. From Wright’s notes, we know the majority of the pottery was obtained from burials. The maps below show the Caddo culture area, and a close up of the archaeological sites that occur in McCurtain and Red River counties.

The Wright Collection contains 685 ceramic pieces. Most are complete enough to have been fully restored. This has allowed for a full study of the different manufacture and design techniques used by Kadohadacho and Nasoni potters. Unfortunately, more detailed knowledge about the pottery is not possible because they were removed without good records of their contexts.

The online exhibit is a showcase of the art of the ancestors of the Caddo. Within the elaborate cultural tradition of the Caddo were ceramic vessels made for daily and ritual use. Daughters learned the art of pottery making from their mothers and this knowledge was passed down for generations. Their beliefs in the everyday and afterlife influenced their construction and artistic design in pottery making.