Describing the Leaves Among the Rocks

By Rick Lupia and Margaret Landis

Long before flowers brought many new colors and insects to our yards, Oklahoma was covered by green plants of a very different sort. Ferns and their botanical allies (mosses, lycopods and other plants that reproduced with spores instead of seeds) grew along streams and in swamps.

Early in Oklahoma’s prehistory, what would become our state was covered by forests and fens composed mostly of these plants. During the late Carboniferous Period (298-323 million years ago), one member of this group—lycopods—contributed literally tons of bark, branches and roots to form what would become the coal seams once mined throughout much of the eastern half of Oklahoma. Paleobotanists and botanists track the evolutionary and ecological history of these seedless plants.

As part of a three-year grant funded by the National Science Foundation, the Sam Noble Museum is participating with 33 other institutions under the leadership of the University of California, Berkeley and Yale University to document the diversity of ferns and their allies, collectively called pteridophytes, represented in collections around the United States. The Pteridophyte Collections Consortium (https://pteridophytes.berkeley.edu/) consists of both herbaria, which collect and curate specimens of living pteridophytes, and paleobotany collections, which collect and curate fossil specimens of living and extinct pteridophytes. The PCC’s goal is to digitize and web-mobilize over 1.6 million extant and fossil pteridophytes to make them web-accessible for researchers, as well as the general public. These data will be used for research, education and public outreach, as well as provide data for long-term digital collection archives.

“Museums are not static places, and they contain a tremendous amount of information that needs to be made available to be shared and integrated with others’ information to help with the pursuit of knowledge and science,” said a longtime Paleobotany Collection volunteer.

The Paleobotany Collection at the Sam Noble Museum is composed of over 100,000 specimens encompassing macrofossils (leaves, stems, etc.) and microfossils (glass slides containing pollen and spores) from around the world, but with the majority from North America, especially Oklahoma. The scope of the PCC grant is restricted to the pteridophyte component of the collection’s 45,000 macrofossils (estimated to be 8,000 plants/taxa).

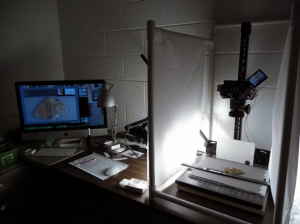

To digitize the pteridophytes, Paleobotany Curator Rick Lupia, Ph.D., ensures that representatives of the various kinds of plants/taxa and time periods are included in the digitization process. Then, Collection Manager Margaret Landis prepares them so that volunteers and a student assistant know what needs to be photographed. Images are captured of the block of rock that bears pteridophyte fossils, in addition to closeups of particularly well-preserved or informative specimens. Each image contains the catalog number of that specimen (in a custom holder 3-D printed by the museum’s exhibits department), a color calibration grid to allow image correction and a scale bar to allow measurements to be taken. As of March 14, the Paleobotany Collection has captured 5,422 photos which represent approximately 1,703 overall slab sides, containing approximately 3,577 pteridophyte fossil specimens.

To accomplish the museum’s portion of this endeavor, the Paleobotany Collection has relied heavily on its generous and capable volunteers to capture images, to enter data and to help recruit and train additional volunteers to assist.

“We appreciate not just being tourists in a museum, but a helper to the museum and to science,” volunteers told Landis and Lupia. “Plus, we enjoy helping create ways for more people to see the massive amounts of specimens that a museum has since the physical space for all of it is not possible.”

Before the Sam Noble Museum closed to the public in late March due to COVID-19, Landis coordinated and supervised 19 volunteers and one undergraduate assistant who work in shifts.

“It’s cool to see that ancient plants look very similar to living plants, and to be able to help document this for others to see,” said the undergraduate assistant.

Despite the unprecedented interruption, work is continuing with data and database cleaning in preparation for uploading to the PCC’s website. Landis and Lupia both hope that photography will resume soon.

“Documenting 8,000 pteridophyte fossil specimens is a lot of work, but one that our collection enjoys being able to involve the public in by inviting volunteers to help,” said Landis.