There are two extinction events in the Permian and the younger of the two, at the end of the period, was the largest in the history of life. It is relevant to the modern world because climate change on a massive scale may have played a role.

When did it happen?

There were two significant extinction events in the Permian Period. The smaller, at the end of a time interval called the Capitanian, occurred about 260 million years ago. The event at the end of the Permian Period (at the end of a time interval called the Changshanian) was much larger and may have eliminated more than three-quarters of species of marine animals. It happened about 252 million years ago and geological evidence shows that it may have taken no more than 200,000 years. In terms of geological time the extinction occurred quickly.

Who became extinct?

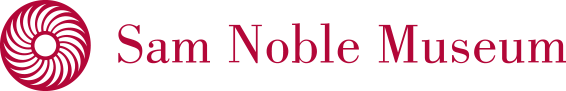

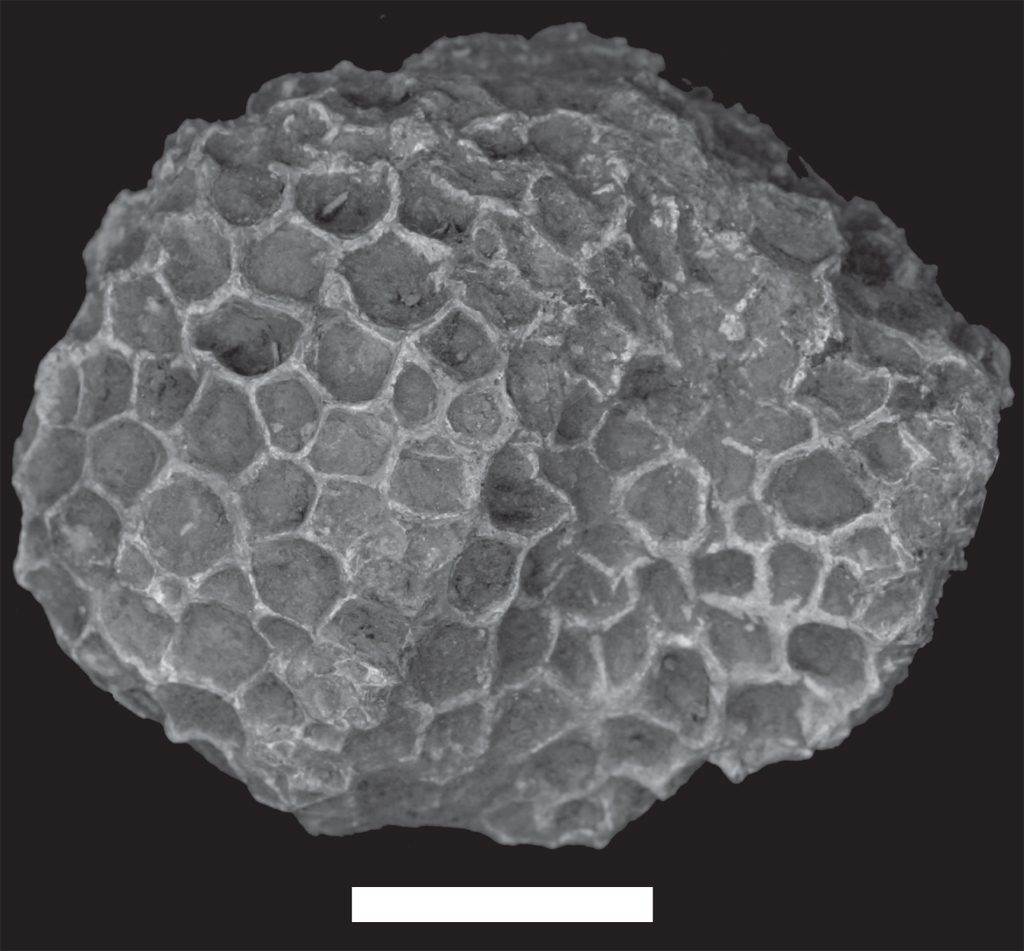

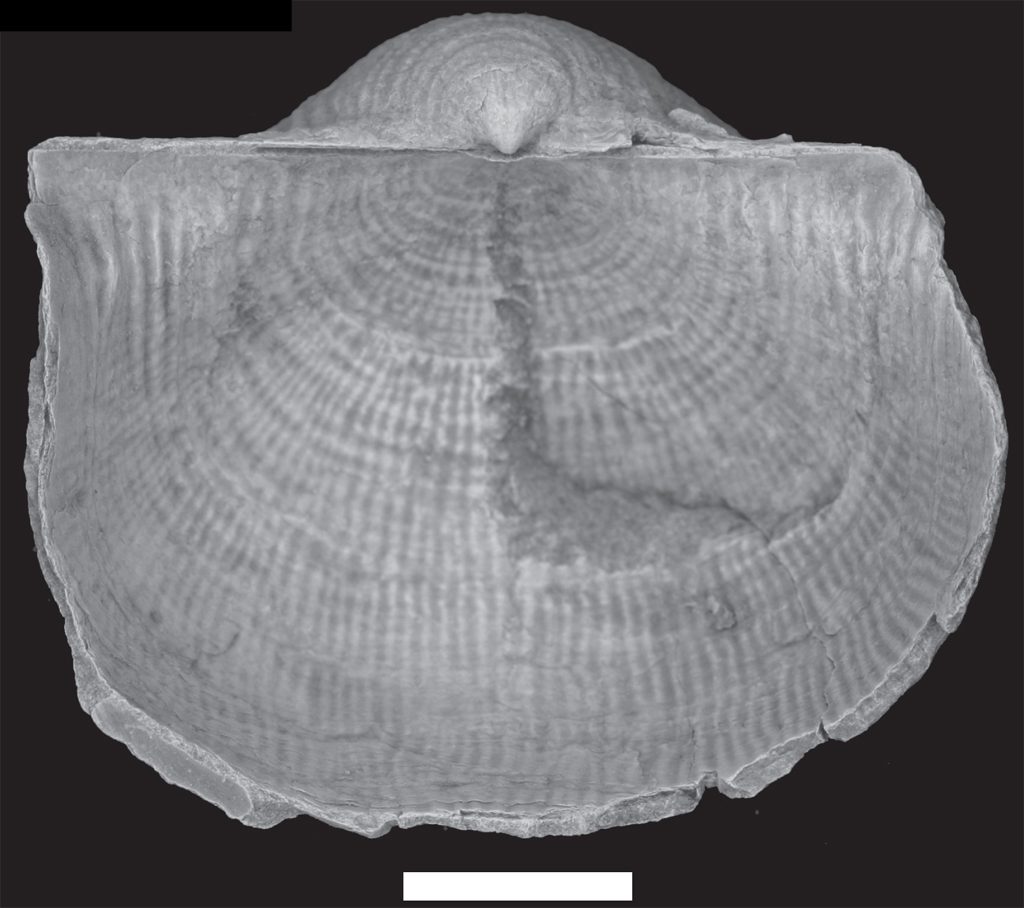

Important groups of marine animals disappeared at the end-Permian extinctions. Trilobites, which had lived in the oceans for more than 250 million years, were lost, along with tabulate and rugose corals. Reef building in shallow seas stopped for about 14 million years until the middle of the following Triassic Period. At that time, an entirely new group of corals, the stony or scleractinian corals, appeared in the oceans. Although they did not become entirely extinct, rhynchonelliform brachiopods, crinoids, shelled cephalopods and snails also suffered significant losses. On land, primitive synapsids (relatives of mammals) disappeared. Some estimates suggest that up to 70 percent of vertebrate genera were lost. Below are some groups of marine animals that became extinct at the end-Permian event.

What caused the extinction?

Warming of the Earth’s climate and associated changes to oceans were the most likely causes of the extinctions. At the end of the Permian Period volcanic activity on a massive scale in what is now Siberia led to a huge outpouring of lava. The eruptions also produced carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that helps warm the planet. The lava flows erupted onto carbon rich rocks like coal and as they were heated by the hot lava, greenhouse gases, including methane, were also produced. The global warming that followed may have increased average ocean water temperatures by as much as 14.5°F (8°C).

Much of the carbon dioxide released by the eruptions would have been absorbed by the oceans. High levels of dissolved carbon dioxide in seawater are toxic to many marine invertebrates. Also, the dissolved carbon dioxide would have produced changes in seawater chemistry that may have made it difficult for some marine invertebrates, such as corals, to grow shells or skeletons. If that wasn’t bad enough, there is also geological evidence that the amount of oxygen dissolved in sea water (which invertebrates and fishes breath with their gills) was reduced, probably as a result of changes in ocean circulation.